Child Aid’s goal is to improve children’s literacy skills so they become strong and independent readers and critical thinkers. Our Reading for Life program follows best practices to provide young readers the basic resources they need to learn and thrive: Skilled and confident teachers, engaging books, and opportunities to read every day, both in and out of school.

Each year, we get more and more enthusiastic comments from teachers, principals, school officials and parents about our program. Demand for Reading for Life is growing exponentially. And that feels great to all of us.

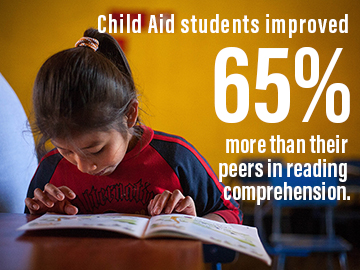

But a key, lingering question has remained: Does Reading for Life actually help kids learn to read? We see and hear evidence of it every day, but how do we know it works? Would they, for instance, do better on reading comprehension tests than students not exposed to the Reading for Life program? Well, it turns out that the answer is YES.

In our main study, we used a test provided by USAID and the Guatemalan Ministry of Education, to test second and third grade students. We tested almost 2,000 students at the beginning and end of school year and measured changes in their reading comprehension skills. Half of the students tested were in schools just beginning the Reading for Life program and half were in matched control schools that did not participate in the program.

In our main study, we used a test provided by USAID and the Guatemalan Ministry of Education, to test second and third grade students. We tested almost 2,000 students at the beginning and end of school year and measured changes in their reading comprehension skills. Half of the students tested were in schools just beginning the Reading for Life program and half were in matched control schools that did not participate in the program.

The results are now in and they are hugely encouraging. Children in the Reading for Life program schools showed a 65% improvement in reading comprehension test scores compared with their peers in similar schools.

These results are statistically significant and showed a strong effect size, meaning that our program is very likely the most important factor in improving student scores. This is an impressive result for an educational program, especially after only one year of the intervention.

There is a lot of research showing how difficult it is to demonstrate that any educational intervention has a strong impact. That is because so much of student performance is determined by things that happen outside the classroom. In studies like these, the calculation of effect size is used to measure how much an intervention contributed to the results. In most studies of educational interventions, effect sizes are rarely as large as .30. In our main study, the effect size was .37.

In a second study, we compared students in the third year of the Reading for Life program with students from non-Child Aid Schools. The students who had been in the program longer also did significantly better than those in the control schools and with a stronger effect size of .53.

These strength of these results were a big surprise and very encouraging for us. They show that not only is our program working but also suggest that the increases in student skills will continue to grow the longer students attend Child Aid schools. It means that the full impact and success of our program is yet to be seen.

This year we are continuing our evaluation and testing, watching schools as they go through the Child Aid program. We are also collecting teacher feedback through focus groups to evaluate the effectiveness of our teacher training workshops and one-on-one coaching. What we learn will not only confirm for us that we are making a difference, but also help us continue to make adjustments and improvements as the program grows.