By Eva Saenz

An Introduction

The contributions that Child Aid has worked to provide for the last twenty years exists within the ecosystem of a complex and interconnected history of Guatemala. In the efforts to provide a comprehensive, four-year teacher training program, Child Aid has focused their intentions towards education within the country. But the education system in Guatemala does not sit alone in a vacuum of common circumstance. Teachers who lack support, children who sit in classrooms without books, parents who never have the opportunity to read to their sons and daughters — these are the results of a country that for decades experienced turmoil from forces both within and outside of the Guatemalan state. Child Aid, and non-profits who sit at the same court lines, are working not only within the context of current education systems and economic barriers. They speak to the struggles of grandparents, fathers and mothers, siblings, who experienced a Civil War, national disruption, and a lack of resources in gaining educational knowledge over the last hundred years. To grasp the landscape that organizations like Child Aid work within, one must venture into its history, both within the Mayan highlands (in which Child Aid focuses much of its work) and within the events that lead this community of individuals into the current 21st century. Centuries of colonial exploitation, civil war, and foreign interventions impact the realms of being that exist – the same realities of current existing that organizations like Child Aid work within today. One that hopes not just to give teachers and students the ability to write their own futures, but the livelihood, the spirit, the joy in order to be able to live them.

General Background

In reaching towards indigenous experiences in present-day Guatemala, one must begin by understanding the vocabulary that preludes the logic. The country’s ethnic makeup is made up largely by the Mayan, Garífuna, Xinca, and Afro-descendent peoples. What we often refer to as ‘Mayan communities’ is really the conglomeration (Guatemala Indigenous Stats) of about twenty-two confederations or fiefdoms that lived amongst different regions of the highlands and

pacific coast (The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics (2011). Spaniards arrived in 1524, conquering these regions under the command of Pedro de Alvarado, second-in-command to Hernán Cortés in the conquest of the Aztec Empire in Mexico four years prior. It wasn’t until 1841 that Guatemala became fully independent under the pressure of a guerilla movement led by Rafael Carrera.

A few years before the insurgency of the Carrera led guerilla movement, the United States enacted the Monroe Doctrine. The doctrine, ratified in 1823, prevented European powers from further colonizing newly independent Latin American countries. But in the same breath, the Monroe Doctrine also gave the U.S. the ability to justify intervention in Latin America (The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications by Mark T. Gilderhus). The doctrine gave the U.S. the ability to define for itself when Latin American countries were in need of intervention, oftentimes in the benefit of American economic growth and worry over Communist sentiments expanding. These founding years would play out in the lead up to Guatemala’s agricultural revolution and eventual exploitation by foreign powers. Agricultural resources and the decisions made in propagating or dissolving support systems (educational, economic, cultural) that held up the indigenous communities would eventually become the impetus for the Civil War in 1960. The Monroe Doctrine would aid the U.S. in meddling in Guatemalan affairs, especially when it came to agriculture and capital that was supporting the livelihood of U.S. expansion.

The United Fruit Company

The United State’s role in inserting itself into Guatemalan agriculture can be seen clearest in the United Fruit Company (UFC). Terms such as ‘Banana Republics’ coined the presence of the UFC in countries all across Central America. Known for their harsh working conditions and coarse means for attaining indigenous highlands, the UFC gained notoriety for being a United States-owned multinational fruit corporation that created export infrastructure in Central America and in the Caribbean . The early 1900s was the golden era for the UFC as many Latin American countries opened their concessions to the company (UFC ). As a response to the displacement towards indigenous communities and harsh labor conditions that the UFC inflicted, a pro-democracy student movement mobilized in Guatemala. This began the 1944 Revolution with Jacabo Arbenz leading the coup against then-President Jorge Urbico.

Jacabo Arbenz was eventually elected President of Guatemala following the term of Juan José Arévalo who began a period of social reform in the country (Bowen U.S. Foreign Polcy Towards Radical Change). Arbenz’ appointment to office came with massive reform policies including Decree 900. This policy aimed to end the cycles of farming areas that were purely sustained for capitalistic means of production. Decree 900 aimed to give and return land to farmers who had been dispossessed after the Spanish invasion. But as the United Fruit Company had gained so much land in Guatemala, Decree 900 was a threat to the company’s continued business. As a response, the UFC lobbied the United States which led to a coup against President Arévalo. This coup and the forced appointment of U.S. supported Carlos Castillo Armas would mark the beginning of Guatemala’s thirty-four year Civil War (Bowen U.S. Foreign Polcy Towards Radical Change 92).

The Civil War

Though the Civil War’s impacts reverberated across the country, the epicenter was largely in the highlands, coast, and capital (BALL State Violence in Guatemala 1960-96). The violence that took place between the government and a range of guerrilla groups resulted in tens of thousands of murdered individuals, largely indigenous to the western highlands (Oettler Guatemala in the 1980s 8). Over the thirty-six year period, nine presidents were in office, each creating a new plan for how to dampen guerrilla groups often through violent means. It is important to state that though individuals were responsible for the decisions and impacts of the graphic violence in this period, the larger issues of imperialism, repression, international intervention and class & racial division all played massively significant factors in creating an ecosystem where these acts of violence could be inflicted and supported by the state. This included the dismal and tremendous deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilian individuals – often farmers, students, and teachers. As many as 600 villages were burned to the ground as a response to guerrilla – and often indigenous-led – insurgency in what would be known as the Scorched Earth Policy (Scorched Earth Policy ). From the war’s beginning to end, indigenous Guatemalans were displaced to highly militarized villages, the Spanish Embassy was occupied by a group of displaced farmers in response to murderous crimes by the state, and the question of genocide against indigenous communities arose. After years of peace negotiations, the peace accord was signed in December of 1996.

Impacts of Civil War on Indigenous Communities

The ending of any war is often only the beginning in its impacts. In the case of Guatemala, the level of state and guerrilla warfare impacted day-to-day systems of education for not just the indigenous but country-wide. Within the indigenous community, which Child Aid focuses its work, wartime violence would further fragment political participation and representation (Warren 1998, 89-93; Baston and Camsus 2003, 271). Pallister ‘Why No Mayan Party?’ 130)) Not only were indigenous-led parties rarely supported (Spence et al. 1998, 36]. Both Birnir (2004) and Martí I Puig (2008); trust in both local and international governments had been burned in the same fires and violence lit during the Civil War (Pallister ‘Why No Mayan Party?’ 131 ).

“Wars are often fought in pursuit of future opportunities, struggles taken on so that the next generation will not have to. But the flawed realities that post generations encounter may radically undermine the hope that survivor generations invested in the better future. These flaws also speak to the intergenerational nature of historical injustice and the fiction constructed around peace as a ‘single line in time’.” Book “Youth in Postwar Guatemala: Education and Civil Identity in Translation” by Michelle J. Bellino State in paper that you highly recommend reading this book to those interested in learning more (written very well) Youth in Postwar Guatemala 3

Many returned from the Civil War’s frontlines to what appeared to be the same villages and homes that they originally left. The end of the war did not mark the beginning of present and felt social reform. Guatemala surely looks much different today than it did thirty years ago when the war ended, but the impacts of the pre-civil war infrastructure continued to have lasting impacts to education systems and foreign-trade reliant economy that had been solidified in previous decades. Today, nearly 40% of Guatemalans are younger than the age of fifteen (Urdal, 2012 Book “Youth in Postwar Guatemala: Education and Civil Identity in Translation” by

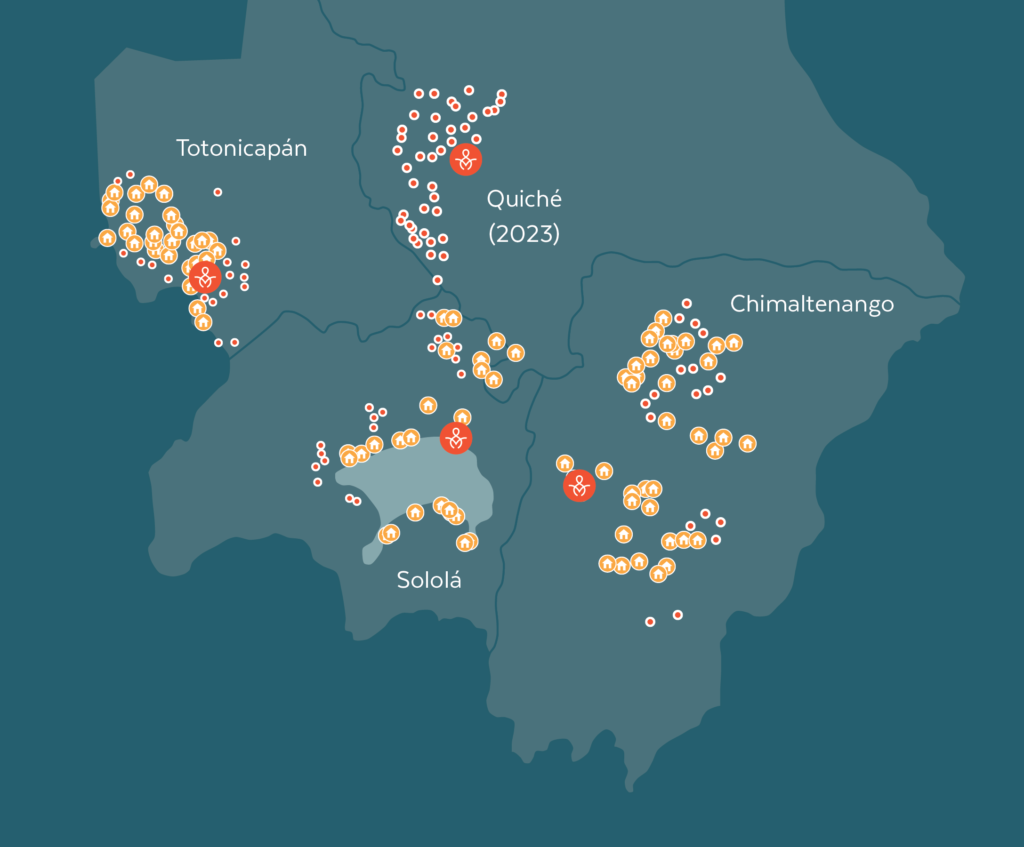

Michelle J. Bellino states: with a large percentage of these youth being out of school or unemployed. The areas in which Child Aid has continued to work are some of Guatemala’s most impacted regions in the aftermath of the war. Hopefully a full lens can provide the context for why work like Child Aid both can be difficult and critical for growing resources in Guatemala. There is much to be said about the interventionist history that the Latin country has experienced, and furthermore the violent repression inflicted on indigenous communities (as well as all citizens) in the country. What Child Aid aims to do now is to give Guatemalans the opportunities to envision their own futures and be supported in the process. The education system is not occurring in a vacuum but within the context of a long battle between indigenous rights, repressive politics, and the struggle of fostering a true reconstruction era that could support the indigenous communities that had suffered.