By Sarah Peller

A new podcast series, Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong, is raising national awareness around how children learn to read, and how popular teaching methods have made it harder for students to develop this integral skill. The series is “an exposé of how educators came to believe in something that isn’t true and are now reckoning with the consequences.”

An Introduction

As an organization focused on teaching children to read, we were excited to listen to this podcast series and share our thoughts and experience with “whole language” methodology. Our organization has dealt with different, but similar lessons in our Guatemalan classrooms and as a former school psychologist in the U.S. and current evaluation director for Child Aid’s programs in Guatemala, I know very well the story that Emily Hanford is bringing to a broader audience’s attention. I’ve seen firsthand the harm that’s been done.

A quick intro/recap of “whole language” teaching

Whole language methods encourage children to “infer” when they don’t know a word: look at the picture, think about the story, look at all the context clues – anything besides actually looking at the letters in the word and putting together the sounds.

If you’re a Gen-X or older (or even a millennial in some cases), you’re probably confused: “what do you mean kids aren’t taught letters and sounds?” That’s right. According to the whole language method children supposedly learn the “whole word.” They should recognize entire words without worrying about what letters comprise the word. But the brain does not work like that. It may look like proficient readers can comprehend an entire word without identifying and interpreting each letter, but the science shows that’s not true.

Studying the way people’s eyes move when they read is an important research area; you can learn more about this research in Episode 2 of the podcast. What’s been found is that early readers really need to look at each and every letter to comprehend what they’re reading. In fact, even proficient adult readers pause to look at groups of letters, not just whole words!

As a school psychologist I was trained to treat instructional methodologies as something that can be tested scientifically. It’s similar to how a pharmacologist tests the effectiveness of different medicines. In both cases we should only be using what works, based on evidence. And for whole language, the evidence is damning. Whole language has never passed the test and has been disproven over and over. But teachers get trained in it, and often they don’t know it doesn’t work. And the whole language method has a certain appeal. It can make kids seem like they are naturally proficient or even excellent readers. But it’s just not the case. For a short span in the early 2000s the Department of Education and the National Reading Panel reviewed decades of studies that refuted whole language methodologies, but teachers’ colleges ignored the evidence.

Why do smart, well-meaning teachers think this approach works?

We privilege top performers and believe our direct experience even when science refutes it.

Our Work

Child Aid works in Guatemala, and Guatemalan schools and classrooms differ from American schools in many ways. You can learn more about that in the Problem section of our website. Many Guatemalan classrooms placed too much emphasis on phonics and hardly any on comprehension or vocabulary. As a result, Child Aid has worked diligently over the years to take a balanced approach to teaching our students to read, focusing on the “mechanical” components of reading (what sounds go with which letters) and also emphasizing the need to understand how words go together to convey meaning.

As the podcast points out, the COVID pandemic shone a spotlight on educational missteps in classrooms around the globe. During the pandemic many kids missed the Guatemalan phonics portion of their learning-to-read journey. Our program was designed to pair with the phonics training that students were getting before arriving in a Child Aid classroom. For the kids of the pandemic who didn’t get that crucial phonics training, this was a big problem.

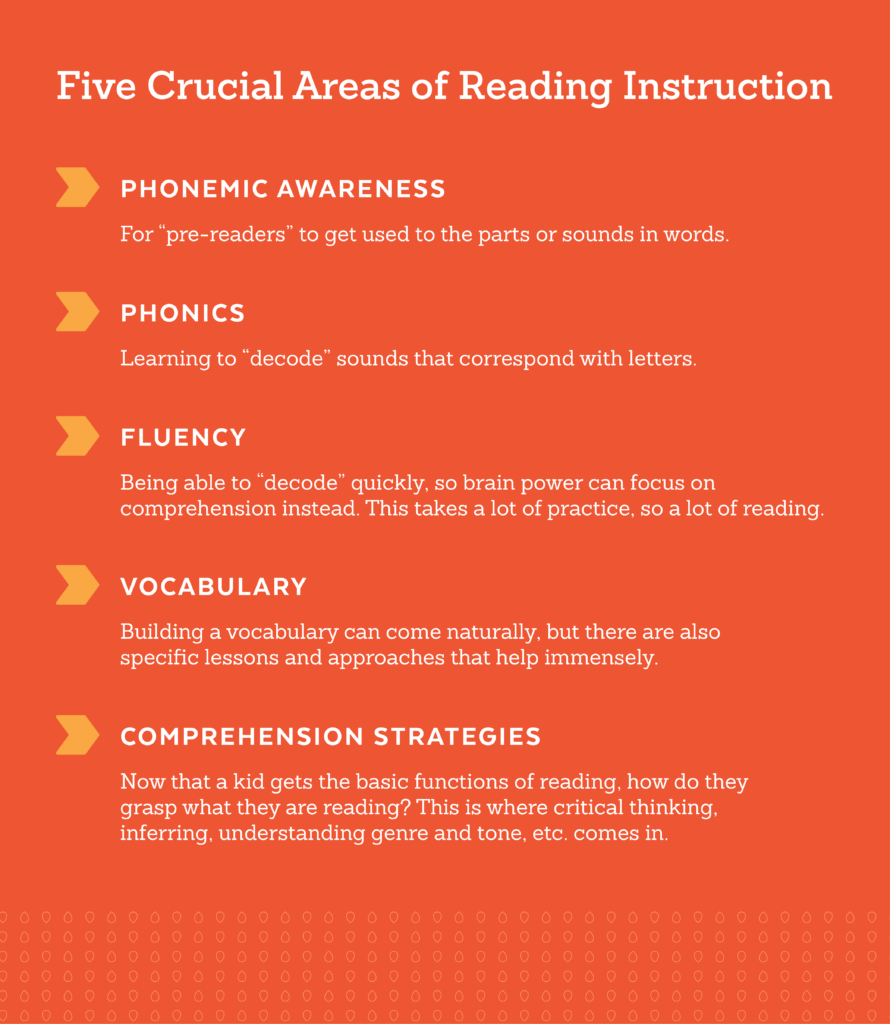

Our team quickly became very conscious of the issue, and Child Aid’s leadership began making changes to our curriculum and staff training to meet the needs of today’s post-pandemic classrooms. As school gets back in session here, our teachers are testing out new lessons that address five crucial areas of reading instruction. Those areas are: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies.

For much of our history, Child Aid has focused on this last step – comprehension strategies. And for good reason. It wasn’t a focus of Guatemalan teaching and it’s necessary for making reading a useful tool in reading to learn and for making it enjoyable.

But Child Aid has been more intentional about adding specific lesson plans to address the first four areas, too. We are evaluating students’ phonics ability so teachers know if they need to spend more time building that skill. We are working on some new fluency strategies and will soon be focusing on clear vocabulary learning approaches. Our team of analysts and researchers are reviewing some of our initial results from these updates- we will write more about this soon as well.

We are excited that Sold a Story is shining a light on this topic and are hoping that it sparks additional research and publication on the techniques that work and the shift that is needed in classrooms in the United States, Guatemala, and around the globe.