The science of reading is having a moment right now, getting major coverage from the Sold a Story podcast, as well as national attention in The New York Times and NPR. Plus, the Trump administration’s gutting of the federal government is endangering programs that work.

So it’s worthwhile to add our perspective on the matter. For those outside of education, how to teach children to read may not seem controversial. But how actually makes a big difference if kids actually learn to read. And when they don’t, they struggle to learn in all areas.

It turns out that many of the ways reading gets taught are not scientifically tested. It can be difficult and costly to carry out the kind of rigorous research that actually evaluates how well a specific program or method teaches kids to read. But it’s necessary, because many popular methods just don’t get results, and they don’t stand up to any rigorous evaluation. (The Sold a Story dives in deep and talks about why one of these popular approaches – whole language – is bogus).

And reading isn’t a skill that most kids just naturally pick up. Children from households where they see a lot of books and get read to a lot, have a leg up and make it seem like they are gifted at reading. But most kids need specific instruction at school. The mechanics of reading – sounding out syllables and matching them to written letters – is just not intuitive.

That’s where the science of reading comes in. This isn’t one particular program. Rather, it’s a set of teaching approaches that have been proven to work with extensive, scientifically sound study. As more and more states in America have realized that their reading curriculum isn’t actually teaching kids, they are turning to the science of reading to provide guidelines about what should and shouldn’t be used in classrooms.

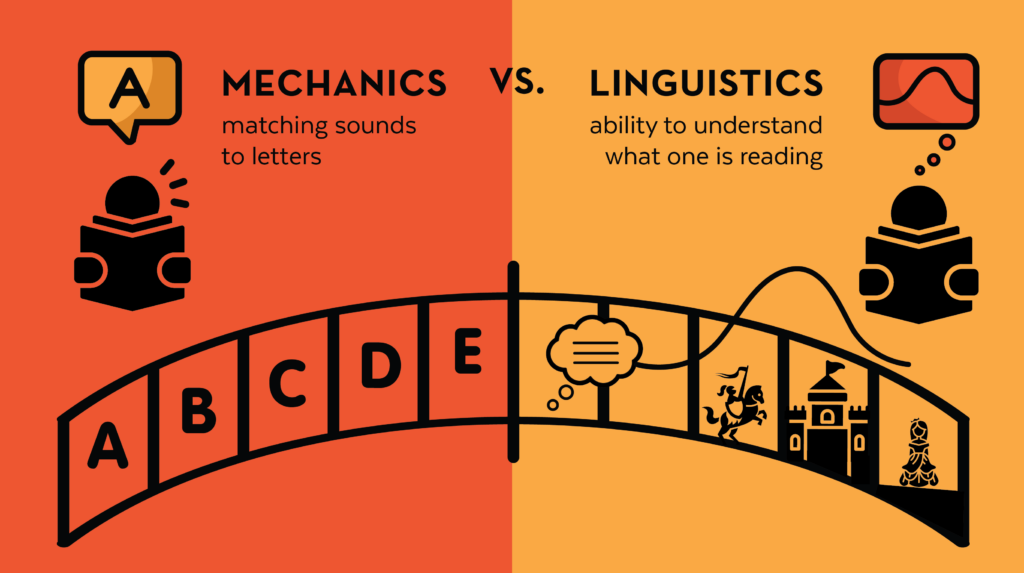

At Child Aid, the science of reading is a valuable way to think about how children learn to read. One of the distinctions that’s important for us is how and when kids learn the mechanics and the linguistics of reading.

What does that mean? The mechanics is the boring but essential part: matching sounds to letters. This allows kids to read new words they’ve never encountered before. And the more they read and practice the mechanics, the better their reading fluency becomes – they can match sounds and letters faster and faster.This is key because if you read too slowly, your brain can’t process the meaning of what you’re reading.

So the ability to do the basic, mechanical part of reading quickly is essential to the linguistic side of reading. This is when you switch from learning to reading to reading to learn.

Much of Child Aid’s educational approach has focused on the linguistic side of learning. This is because the Guatemalan government has traditionally focused only on the mechanics, pretty completely neglecting the comprehension and reading to learn part of things. But research Child Aid did to assess learning loss during Covid, uncovered how much teachers also needed support on how to teach the mechanical aspects of reading. So Child Aid has been adding more of that learning into our program – guided by science of reading best practices.

We are also being clearer about when teachers need to give instruction – where kids are listening and responding in a group – versus when kids need to work on their own to practice essential skills. The balance of the two is key: students need the right instruction and tools and enough practice time to succeed at reading and literacy.

The developments in the science of reading in the last few years are exciting and will lead to major breakthroughs in literacy levels – in America, Guatemala, and beyond. At Child Aid, we know our program works, and we are always evaluating where and how to make improvements that are informed by our cultural context and scientific rigor.