Carlos Pos Ben is a Child Aid literacy trainer and a native speaker of Kaqchikel, one of Guatemala’s 21 indigenous Mayan languages. He works in several remote Kaqchikel communities in Guatemala’s Central Highlands, helping undertrained teachers in neglected schools become better bilingual educators.

Most of the more than 50 towns and villages where we work are indigenous. Children in these communities speak Mayan languages – K’iché, Kaqchikel and Tz’utujil – and enter school speaking very little Spanish. Because books are out of financial reach for their parents (and because most of their parents cannot read anyway), the majority of the children we work with have minimal, if any, experience with books. When these kids enter school at age 5, they face incredible challenges when trying to learn to read.

Through our Reading for Life literacy program, we pay special attention to these children by employing and training local, indigenous staff and by creating reading activities and programs that incorporate children’s first languages. Through the hard work of our bilingual staff, we arm undertrained teachers with applicable and effective bilingual education skills that can change children’s lives.

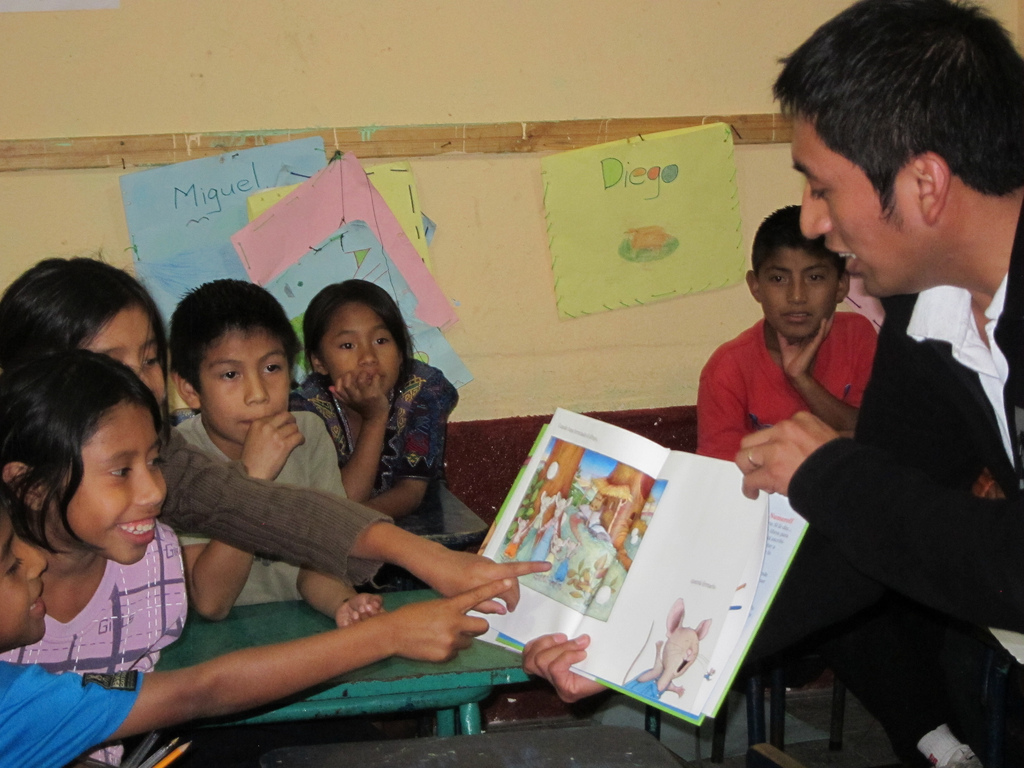

Child Aid literacy trainers visit hundreds of classrooms every year. One of the key things they do during their classroom visits is demonstrate how to read Spanish-language storybooks using two, sometimes three languages. (Very few books are published in Mayan languages.) Most rural teachers lack training in teaching children to read, and they find it difficult, if not impossible, to engage their students. The result is that indigenous children fail to learn to read well, and many drop out early.

“It doesn’t matter how many books you deliver to a school,” explains John van Keppel, Child Aid’s National Director in Guatemala. “If you read a story in Spanish to a classroom of first graders who are still struggling with Spanish, you’ll get minimal comprehension, minimal participation and lots of frustration.” By delivering quality children’s books to rural schools and helping teachers develop bilingual teaching skills, we change the old narrative altogether.

In a country like Guatemala, where illiteracy runs deep and resources are few, getting children to engage in books is critical to creating readers at an early age. It’s imperative to turning at-risk children into active, participatory students who will have a far better chance at succeeding in school.

“If you ask the kids in Spanish what color the big dog in the story was,” explains Carlos, “they’ll say ‘red.’ At most. But if you ask them in Kaqchikel or K’iché, they’ll tell you that the dog is red, that their own dog is brown, that their neighbor’s dog ran away last week, and on and on. They relate the story to their life, and they suddenly have an interest in it.

By giving primary-school teachers straightforward teaching techniques like this, we help

kids develop literacy skills that are fundamental to lifting themselves from poverty.

If they develop those critical thinking and comprehension skills in their mother tongue, they can easily transfer them later to Spanish, the language of commerce and higher education in Guatemala.

“If you wait until these kids are in seventh grade – if they make it to seventh grade – it’s far more difficult to teach these types of skills,” explains John van Keppel. “Most indigenous kids come to school and they’re completely lost. But when we help their teachers expose them to stories and activities in their mother tongue, they light up. They jump out of their seats. Then they plow head-first into school. It’s amazing to see.” These are the results we want, and they are the results we see from Reading for Life.